History Project

Introduction

This account of the history of settlement and development at Clear Lake in Field Ontario is based almost entirely on primary source material: government and business records, photographs, and first-person accounts from current and former residents. Municipal addresses reflect street numbering introduced in 2001.

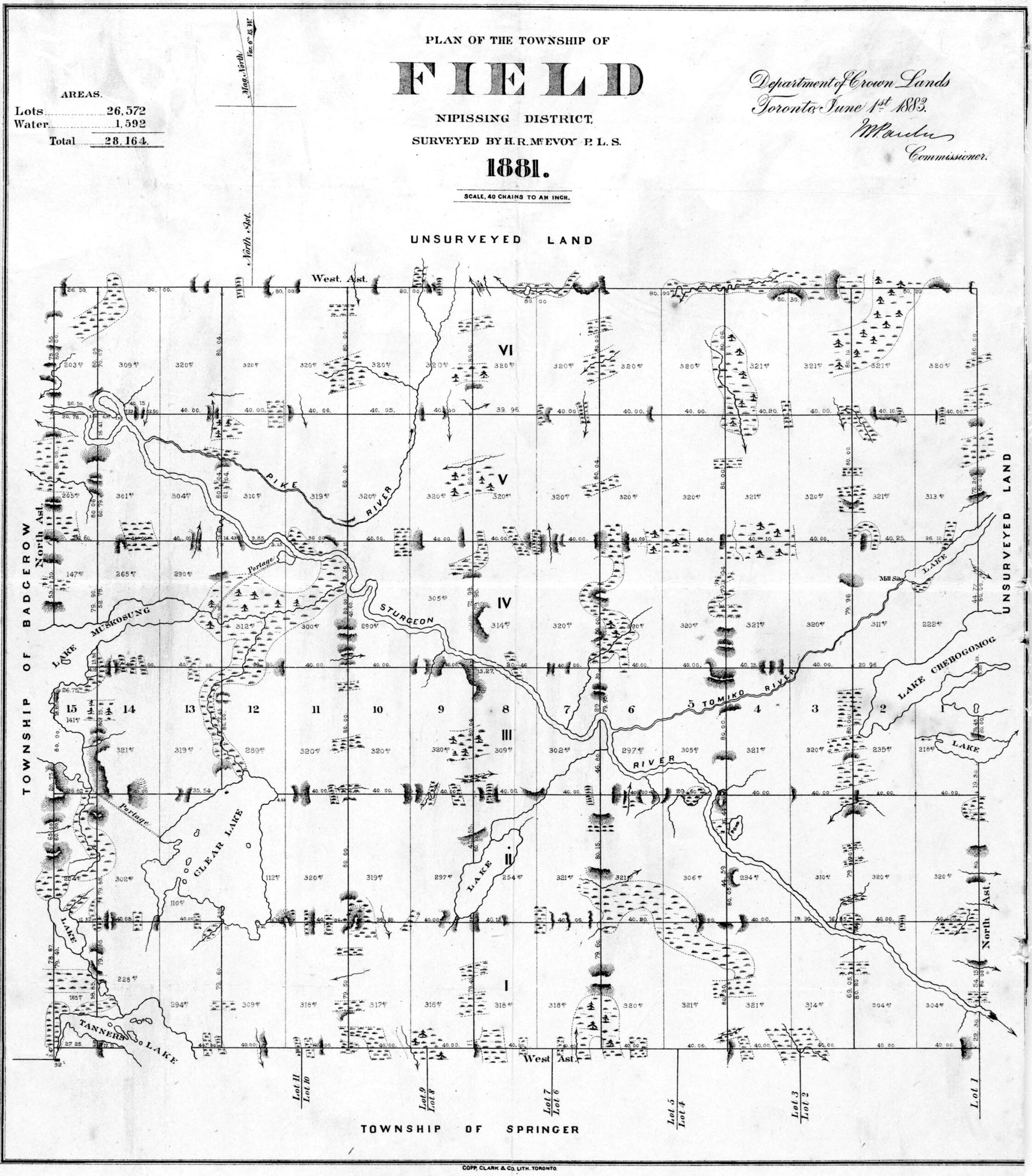

Settlement

By the time that the square timber trade took off in the Ottawa Valley in the early 1800s, the voyageurs and European settlers already had a thriving fur trade with the Nbisiing First Nation, operating from a Hudson Bay Company trading post located next to Lake Nipissing at the mouth of the Sturgeon River.

As early as 1830, logging operators were working a nearby bay that voyageurs called “Cache.” However, the unsettled areas north of Lake Nipissing would remain untouched until 1872 when Ontario began selling cutting rights to the red and white pine forests encompassing the new Township of Field.

Lumber Baron J.R. Booth was already working the Cache Bay area when the Canadian Pacific Railway established local operations in 1882. Four years later, he purchased cutting rights to additional areas in the north that included Clear Lake.

By then, small settlements were opening up in Field Township. A church, post office, general store, tavern and school were operating near the Sturgeon River. The Sturgeon Falls-Martin River Trunk Road was the only roadway to the north until the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway offered passenger service in 1918. Highway 64 would open in 1937.

In 1900,

the George Gordon Lumber Company bought the mill in Cache Bay. According to Richard Filion, around 1902, lumberjacks began using a very rough dirt trail referred to as Chemin Automne or Fall Road to access timber north of Cache Bay. The pristine water in our spring-fed lake led workers to call it Clear Lake. The trail from Cache Bay would later be officially named Clear Lake Road or Chemin Lac Clair.

Booth’s plans included operations in and around Clear Lake. Maurice Giroux recalled as a child speaking with friends of his family, the Roys, who were employed by Booth in 1905, and had spent a winter in a tent on the east shore of Clear Lake. They described log buildings, a dam designed to raise the lake water level, and a log slide that had been erected near the outflow creek (running under the current North Shore Road). Logs were stored in the lake, then hauled or floated to the Sturgeon River and on to Lake Nipissing.

Hector Mayotte heard similar accounts of Booth’s operations; Barry and Mike Noland, and Len Tighe have located deadhead logs displaying the “J.R. Booth” brand in the lake. Maurice’s son, Paul Giroux, recalls seeing remnants of those logging operations in the bush adjacent to North Shore Road when he was young.

J.R. Booth discontinued operations in 1911 when all of the larger pines had been harvested. After his departure, several other operators, including the George Gordon Lumber Company and Mageau Lumber, continued working areas outside Clear Lake. In 1914, the Field Lumber Company was chartered and one year later, the municipality of Field was incorporated.

These turn-of-the-century logging operations revealed the natural beauty, tranquility and hunting opportunities of the area and sparked the interest of six Cache Bay men.

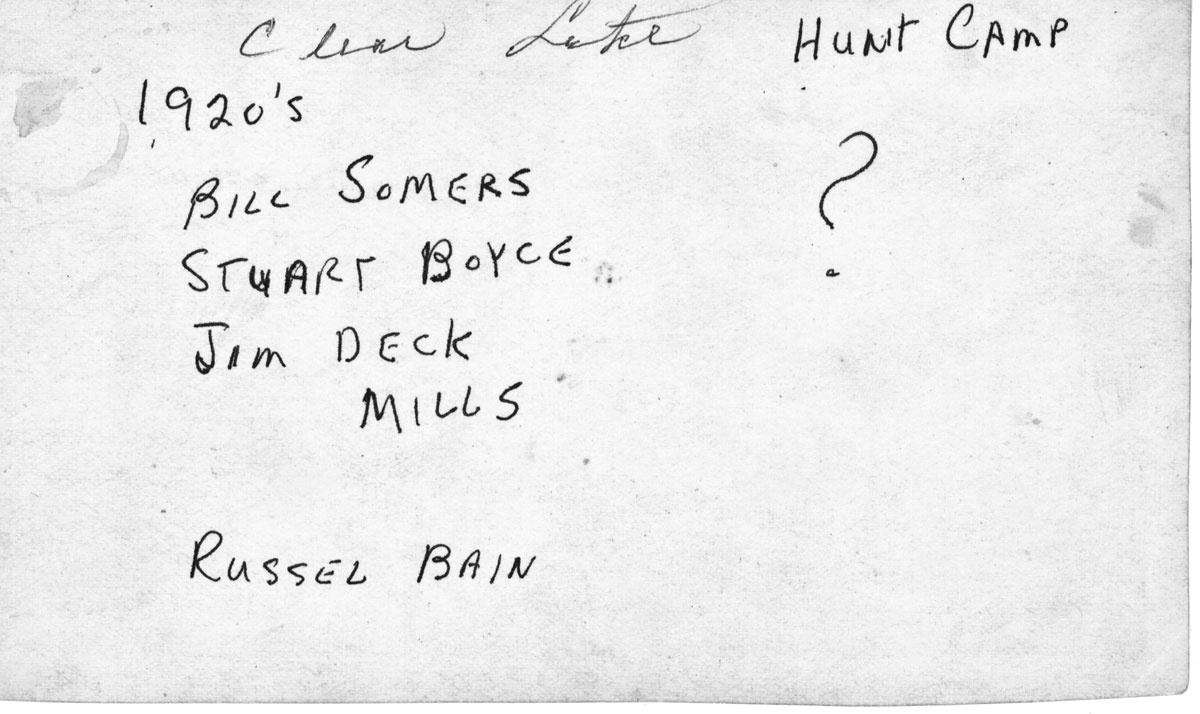

In the early 1920s,

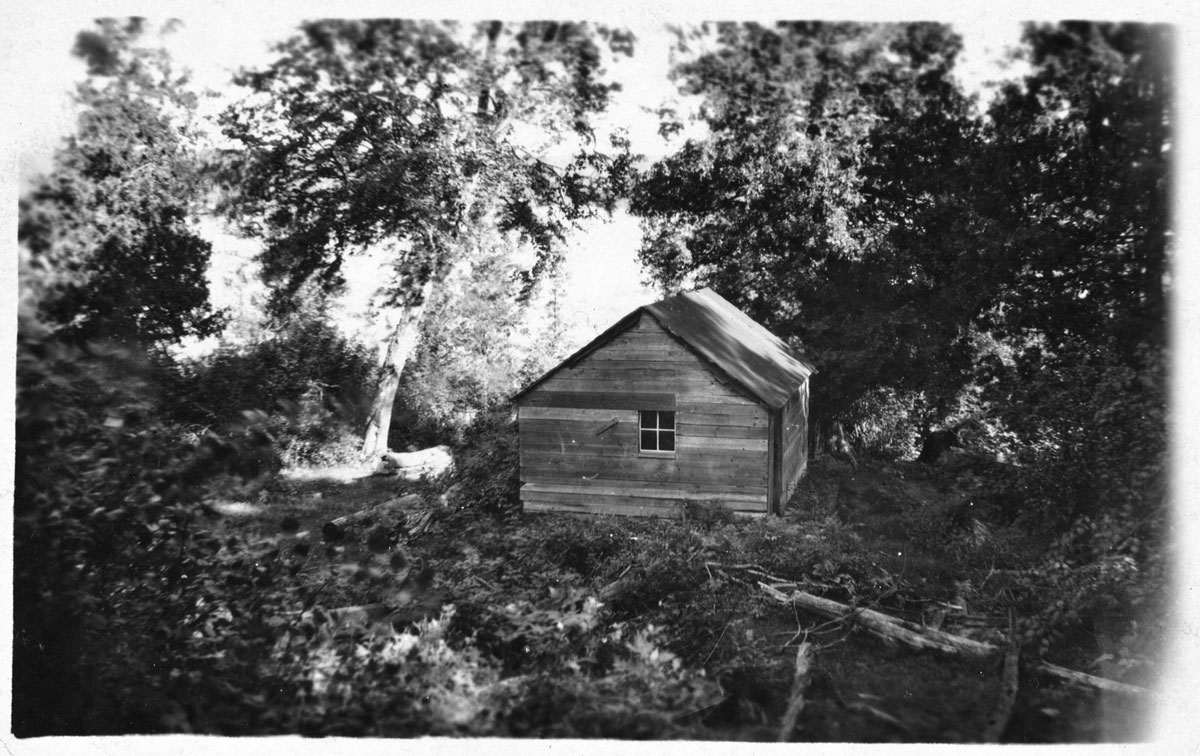

William Somers (then Cache Bay CPR station agent), Russell Bain (then George Gordon mill operations manager), William Morrissey, James Deck, Alex Mills and S.P. Boland built a small hunt camp on the eastern shore of Clear Lake on the site of the existing Tighe cottage at 1115 Clear Lake Road. The camp was used for fishing and hunting deer and small game until interest in the hunt camp waned in the later 1920s. This cabin no longer stands.

Michael Legault recalled his father Louis explaining what life was in the 1920s. Louis Legault lived in Cache Bay, but was employed at a lumber camp near River Valley. To get to work, he walked up Clear Lake Road to Clear Lake, fished for lunch and walked on to the logging camp to be ready for work the next day.

Clear Lake Road Development

According to Peter Bain and Mary Dobson, the first cottages built on Clear Lake were erected on the point off the eastern shore at the southeast end of the lake.

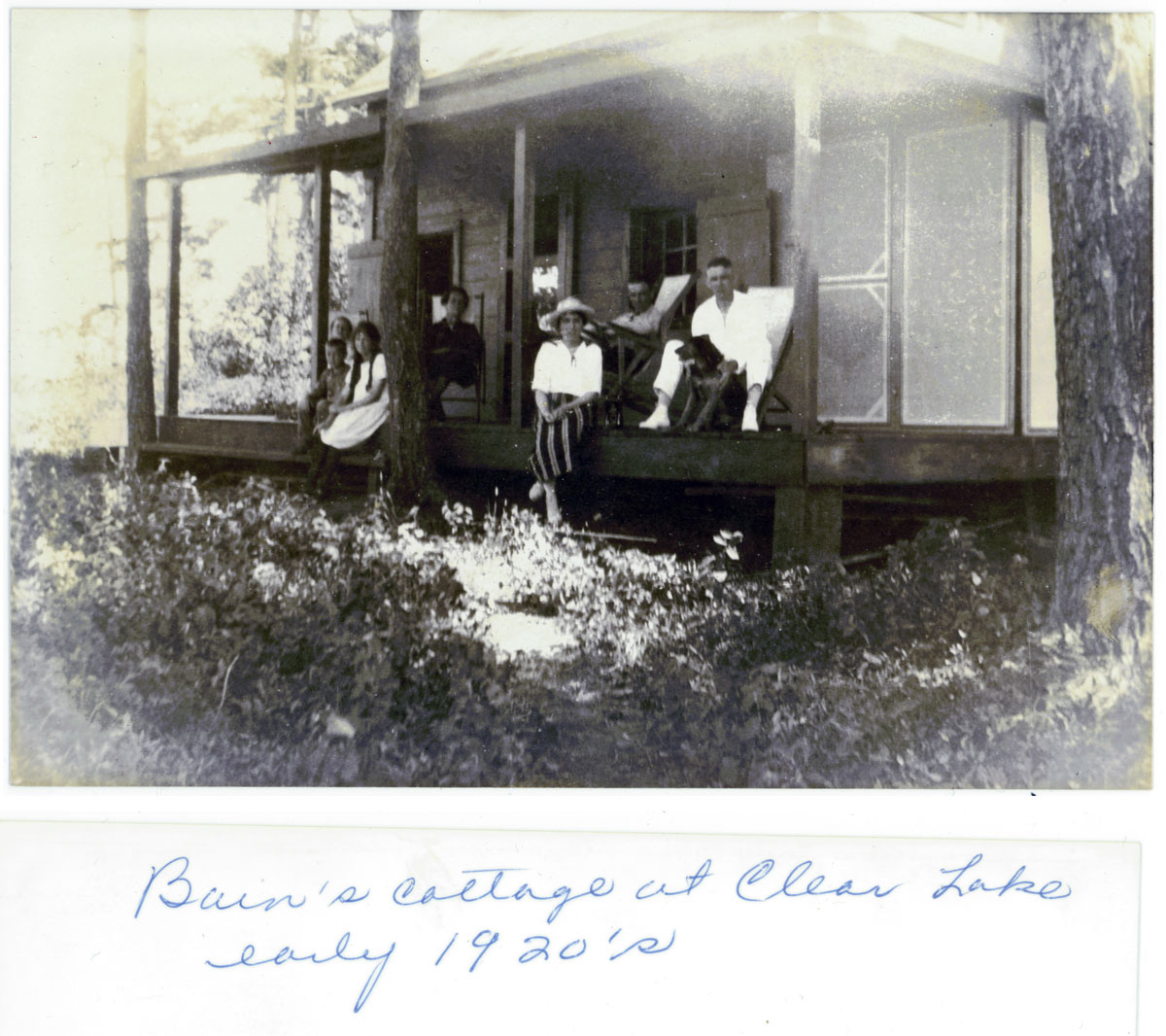

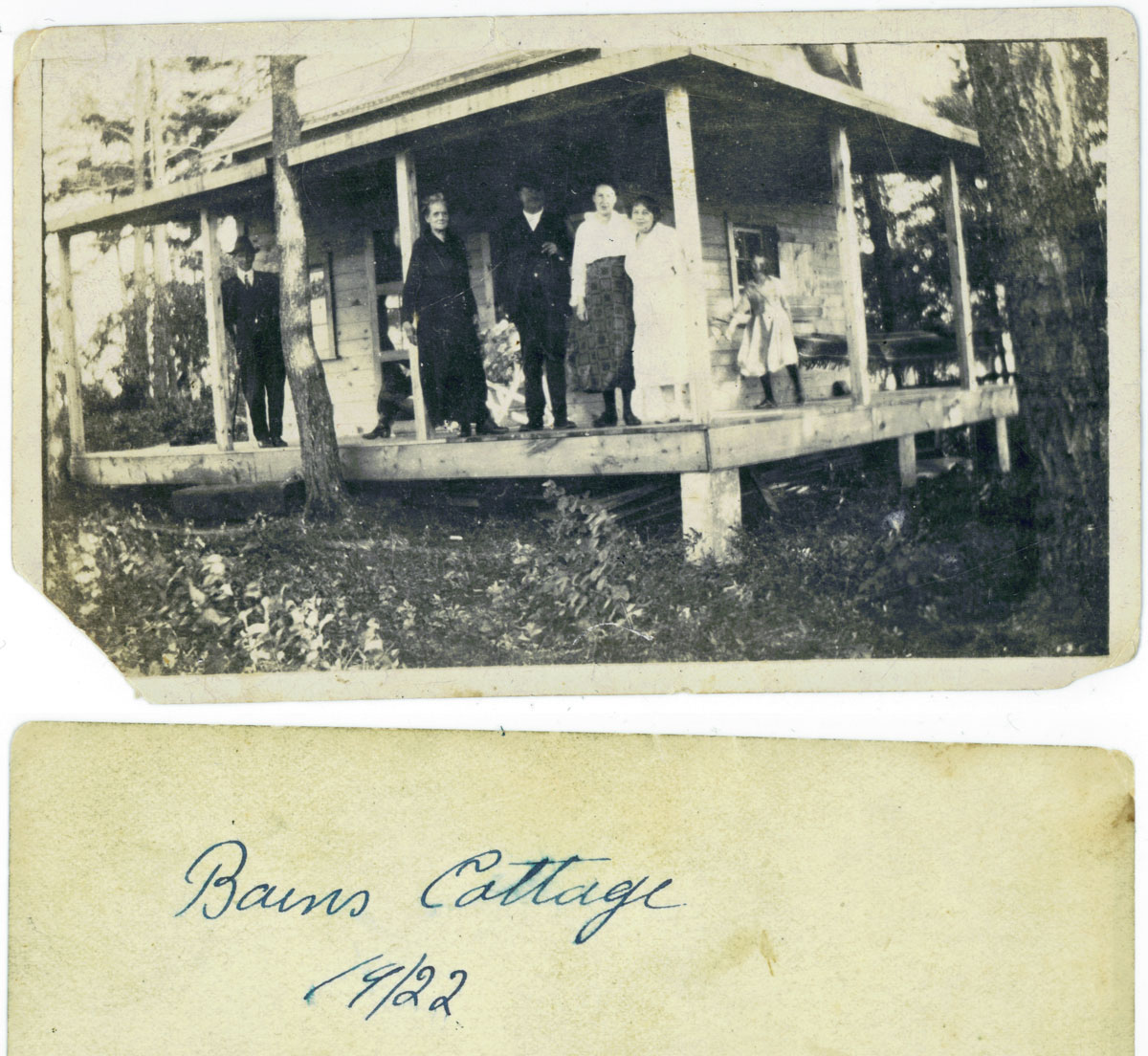

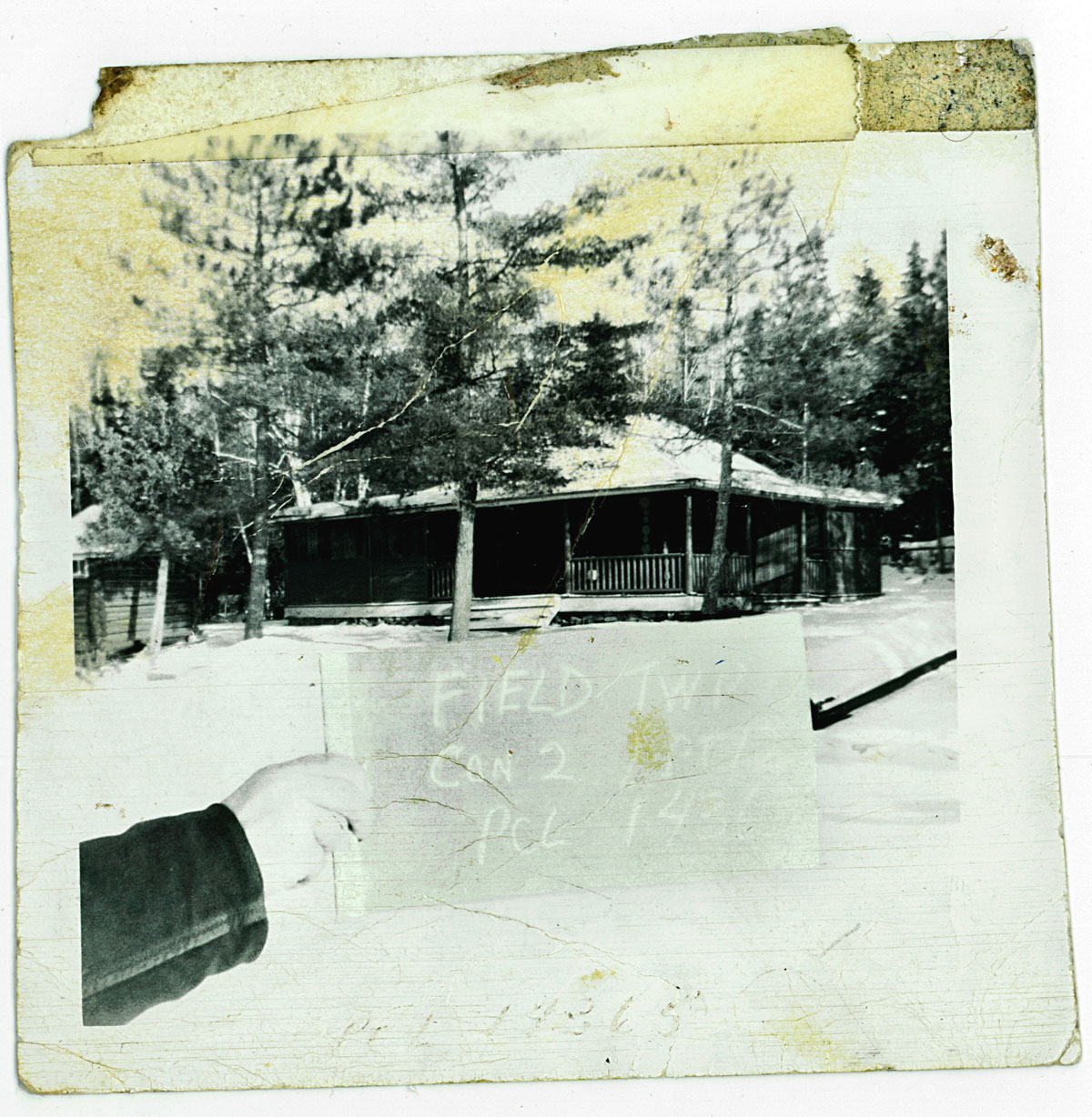

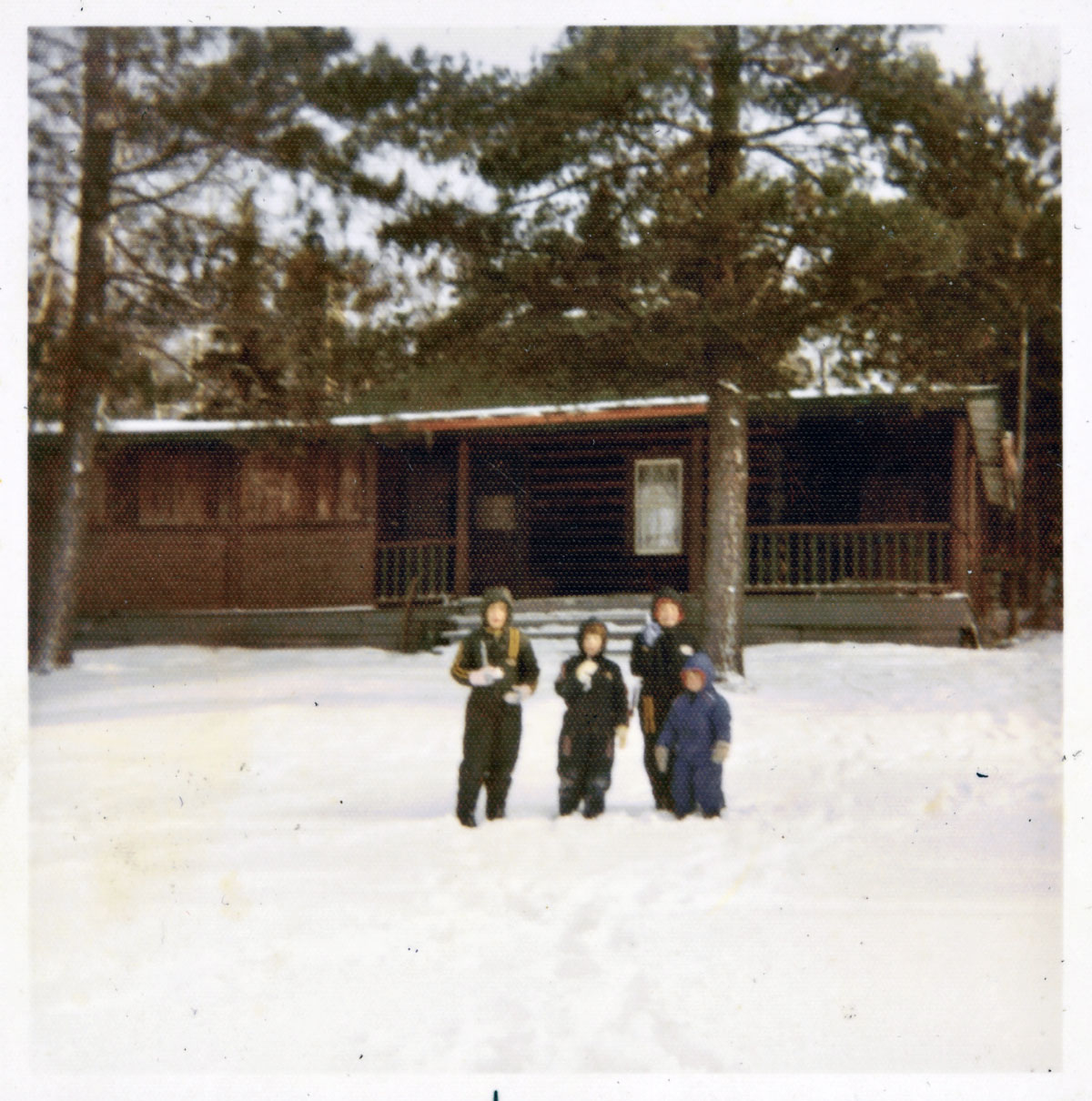

In 1925, Bower Bain, president of George Gordon Lumber, his brother Russell Bain and Nevin Smaille, all residents of Cache Bay, built four buildings at 975A, 975B, and 975C Clear Lake Road.

Bower built a cookhouse and a separate cottage, which were eventually acquired by his sons Howard and Dr. Harry Bain. The cookhouse, Howard’s cottage, has since been removed and replaced with a full-time home owned by Howard’s daughter Judith and her husband Zane Legault.

Dr. Harry Bain and his family enjoyed his cottage for many years. Dr. Bain became one of the most respected pediatricians in Canada and was awarded the Order of Canada for his work as Physician-in-Chief at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children and instigator of the Sioux Lookout Project. In Dr. Bain’s words, that project was “a collaborative one in which universities, governments, doctors, dentists, nurses, communities and consumers participate… [in]…delivery of health care in a remote area under extremely adverse conditions.”

Today, his cottage has been removed and his son Michael Bain and wife Jennifer enjoy a newly built cottage at the end of the point where the original Smaille cottage once stood. The Lalonde cottage in the bay on the north side of the point (975C Clear Lake Road) replaces a second cottage that the Smailles had built while living on the point.

Russell Bain’s cottage is still in use, making it the oldest building on Clear Lake. The upgraded cottage is now owned by his grandson Peter Bain and his wife Donna.

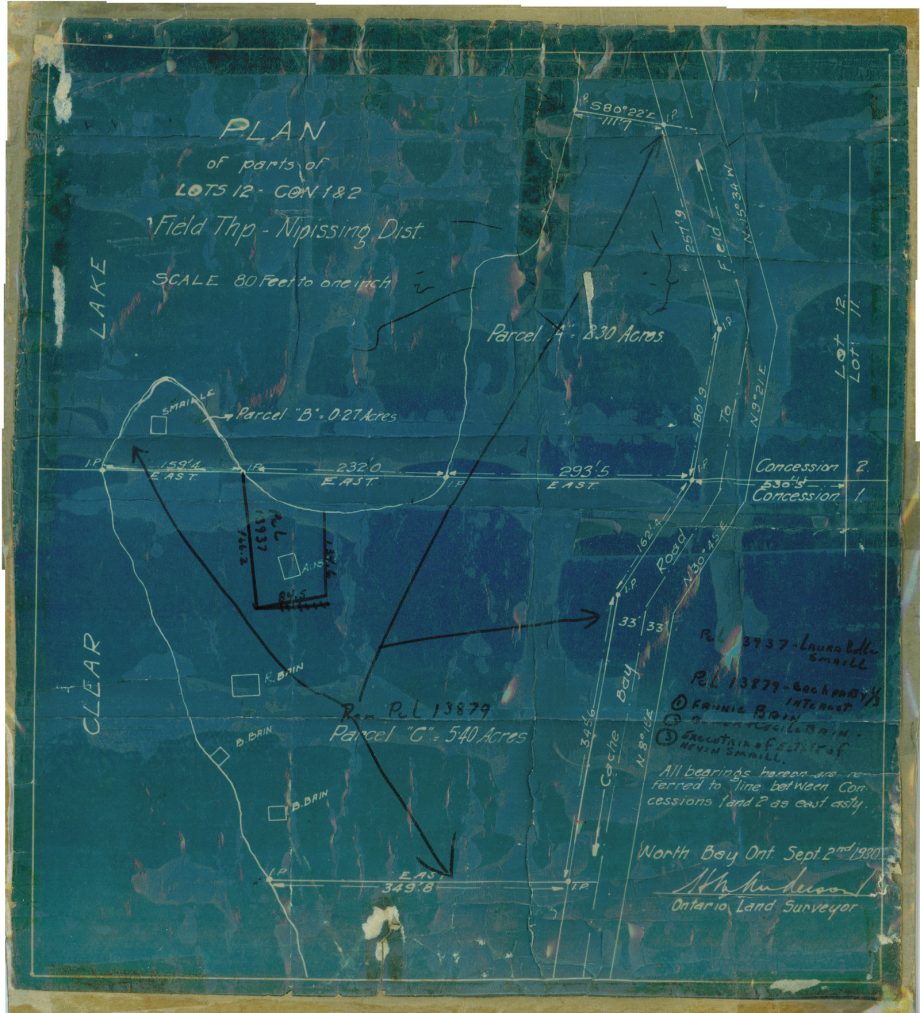

From as far back as 1930,

land surveyors had been surveying individual lots on the lake; by 1947, the Ministry Field Lake Plan was in place.

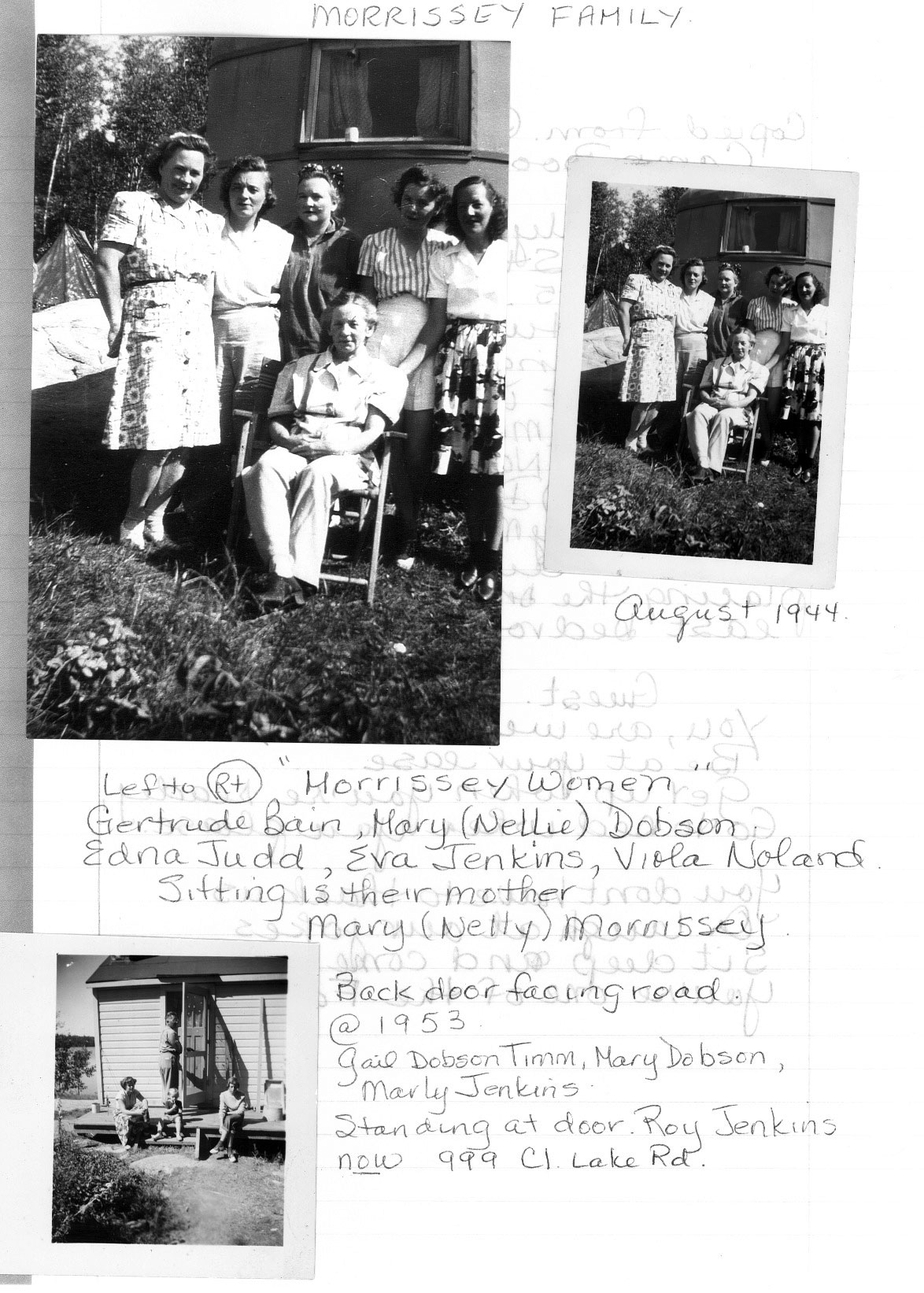

Mary Dobson related that in the late 1930s, her grandmother, Mary (Nell) Morrissey and her five girls, Edna (Judd), Gertrude (Bain), Viola (Noland), Mary Helen (Nellie Dobson) and Eva (Jenkins) spent summertime camping in the bush at present-day 999 Clear Lake Road. The family would travel from Cache Bay along Clear Lake Road and routinely stay overnight at Clear Lake in tents. Granny (Nell) Morrissey would cook homemade bread and meals on an outside cook stove while other family members camped on the adjoining beach area open towards the point that the family fondly referred to as “Granny’s Beach.”

In 1932,

William Somers built a log cottage closer to the northern end of the east shore at 1115 Clear Lake Road after completing a lengthy battle of entitlement with the Department of Lands and Forests. At that time, land cost $10 per acre, and people often built before filing an application in order to avoid the legal requirement to erect a building valued at a minimum of $500 within 18 months of obtaining the permit. William Somers’ original log cabin no longer stands, but the stone fireplace and old log icehouse that was used to store ice-blocks in sawdust still remain on the property now owned by William’s great-grandson Chris Tighe and great-great-grandson Joel Tighe.

William’s granddaughter Jo Somers located a 1936 listing by the Lands and Forests Survey Branch identifying our lake as one of 12 referred to as “Clear Lake” in Nipissing and adjoining districts. Sometime thereafter, our lake was officially named “Bain Lake,” recognizing Russell and Bower Bain as the original patentees of land on the lake. While the lake is identified as such on maps to this day, many continue to use the name “Clear Lake” or “Lac Clair.” This later became an issue with municipal signage. Also, over the years North Shore Road was referred to as “Bain Road” on many survey plans.

Peter Bain started coming out to spend time with his grandmother Fanny Bain (née Harrison) in the late 1940s. He visited on weekends when attending school and full time during summers. He has fond memories of his time with his cousins and other family members, and recalled that in the early 1950s, even before the beach became public, area children were bused to the lake to swim. He remembers the Sunday ritual of going out on the lake to troll and catch a pike for family supper.

Back then, protecting the ecosystem was not high on people’s agenda. Outhouses were placed where convenient, water was used straight from the lake, garbage was burned rather than trucked away, and practices that are frowned upon today were commonplace, such as washing in the lake. Standing under the eavestrough was a handy way to wash your hair.

On one occasion in the early 1950s, Peter’s cousin Billy Bain, an RCAF pilot, caused a stir in the area by buzzing Clear Lake and the Field area in his Sabre jet. Billy’s low-flying manoeuvre, which he thought would impress his father at work at the Field Mill, instead rattled school windows and caused considerable public upset.

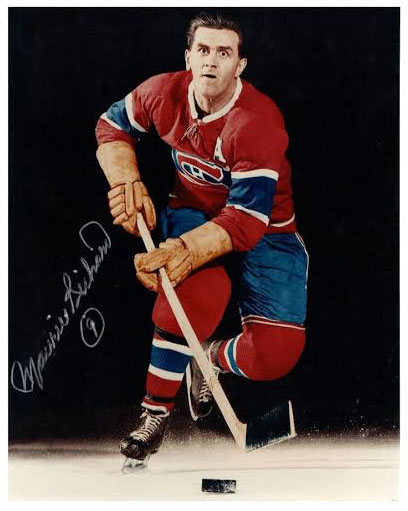

Around that time, Peter’s father Rowan Bain was helping Gerald Arcand, owner of the Sunshine Motel, organize a Dominion Day fundraiser in Sturgeon Falls. Maurice (Rocket) Richard of Montreal Canadiens fame was the celebrity guest and was later invited to attend the Bain cottage on Clear Lake. Peter, who was very young at the time, told his dad that he was a Maple Leafs fan and therefore would not come out of his bedroom to meet the Rocket! He regrets that to this day.

Peter recalled some tragic events: when he was young, Howard Bain’s five-year old son David drowned while swimming off “Clean Beach” in front of 975 Clear Lake Road. Many years later, a snow vehicle fell through the ice near the public beach, and an adult operator drowned.

Barry Noland, Viola’s son and grandson of William and Mary (Nell) Morrissey, recalled that William was injured in a fire while working at the George Gordon mill and later died in 1940. Barry says he and young Billy Bain watched the funeral procession in Cache Bay, with a team of oxen pulling the hearse, a common sight in those days.

In 1945,

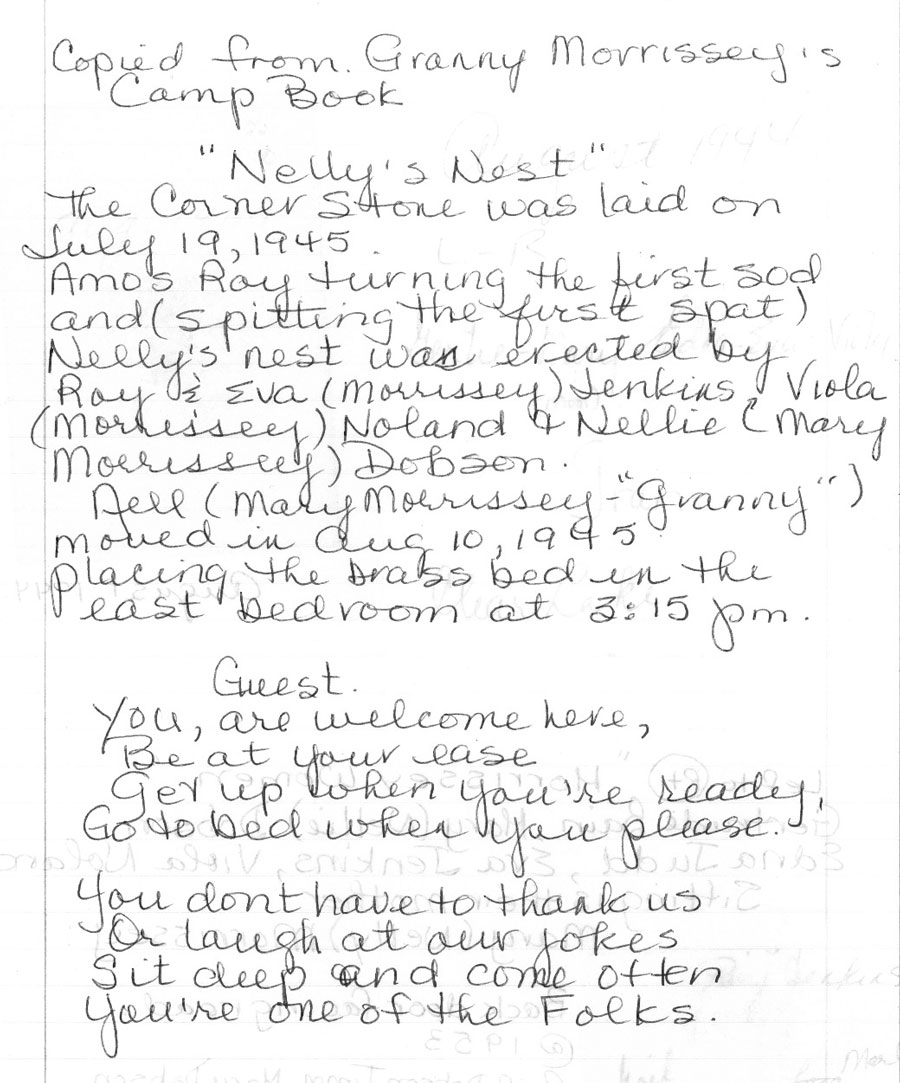

Granny Morrissey arranged to have her sons-in-law Roy Jenkins, a Toronto carpenter, and Mary’s father Wellington (Dobby) Dobson build a small pine camp for her at 999 Clear Lake Road. The pine for that camp was cut and milled locally and drawn to the camp by a team of oxen owned by Amos Roy, a farmer from Clear Lake Road who also laid the cornerstone for the new camp.

Amos and Dobby were at work installing the camp roof on Friday, May 10, 1945, when Nellie Dobson came up from the shore and advised them that WWII had ended. The builders patriotically celebrated VE Day by stopping work to drink six Old Vienna beers that they had been keeping cool in a butter box buried onsite!

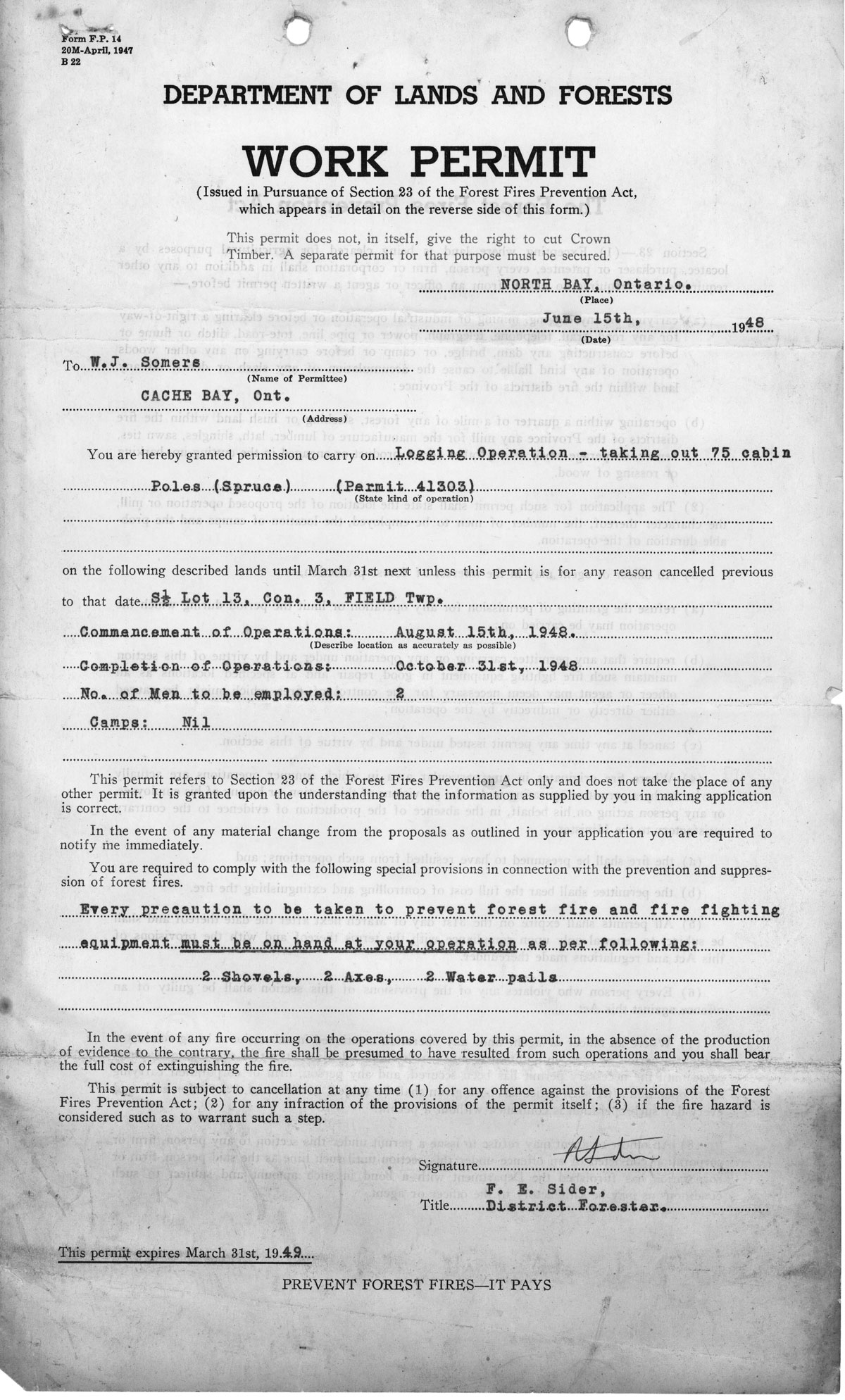

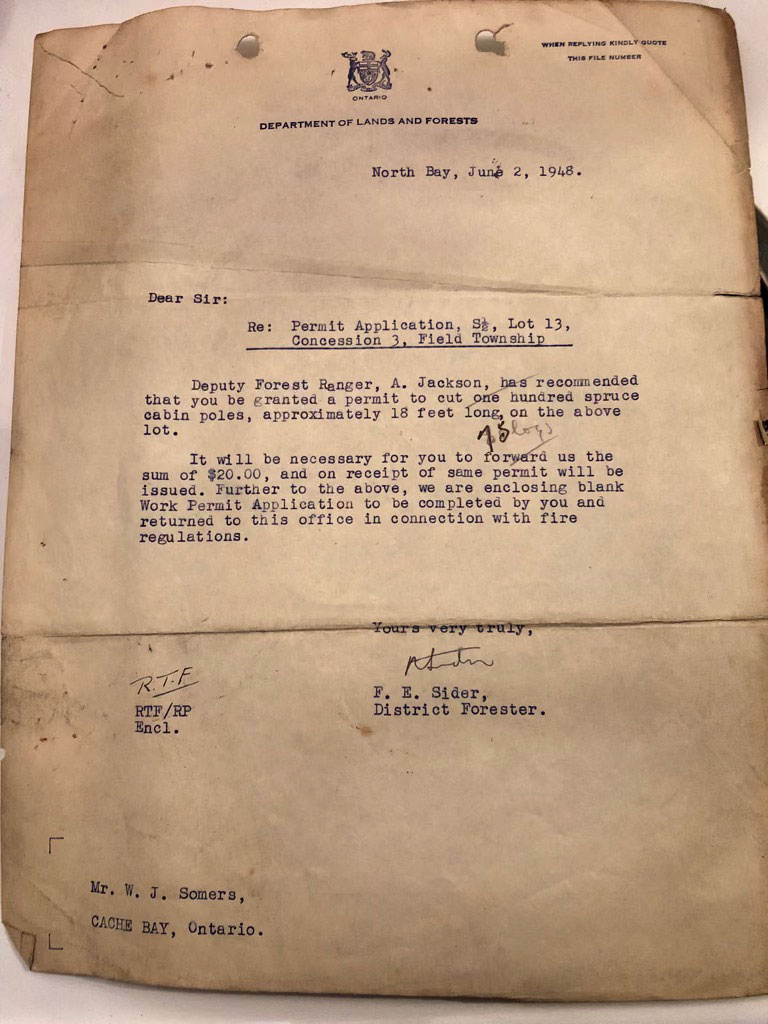

In 1947,

William Somers obtained a permit to fell and log out 75 spruce logs to build a second small cottage north of his original building. William’s son Clive, Tony Coroux and Pat Trahan built a log cottage at 1121 Clear Lake Road. This well-preserved building is presently owned by the Zwarych family. It is the second oldest building on Clear Lake.

“In those days, camps were camps. Now they call them cottages.”

In 1951,

Homer and Marie Smith, Carole Anne Friedrich’s parents, rented William Somers’ original cottage at 1115 Clear Lake Road. It had a screened-in porch big enough to sleep six children. For the next seven years, from 1952 to 1958, the Smith family rented William Somers’ second log cabin at 1121 Clear Lake Road. Carole confirmed that this set the seed for her to eventually purchase on the lake.

When the Smiths were initially renting the Somers’ cottage, the Head family owned the small island in the northeast end of the lake that was later owned by the Forbes. She and the Hope kids used to swim from the eastern shore all the way to the island and back. The kids learned to waterski behind her dad’s cedar strip boat, balancing on their old outhouse door that their father roped to the boat and motor.

Carole Anne’s first trips up Clear Lake Road to the cottage were in a Ford Model T with her Dad. She has fond memories of fishing off the rocks with her father and pole-rafting around the lake. Her Dad told her the lake had been stocked with bass in 1945.

The Morrissey cottage at 999 Clear Lake Road has been upgraded, and still stands. Barry subsequently acquired the cottage from his mother Viola; ownership was later transferred to Nell’s great-grandson Michael Noland and his wife Allison.

Clear Lake Road connected Cache Bay to Highway 64 at Field, but the road was not good. Mary Dobson and her family would carry planks in their car to put under the wheels when they got stuck in the mud. Getting past Tanner Lake (Lac Tonnerre) was always bad. As a child, she would stand up on the back seat of their vehicle if they should happen to drive up behind Mr. Somers. He drove slowly and you couldn’t pass, so she knew it could take an hour to get to the camp!

When Mary first started cottaging, there were only a few buildings on the lake: the Lavergne cottage next door at 1005 Clear Lake Road, the Bains’ on the point, the Somers’ and a few others. She recalled a big hunt camp at the west end of Northshore Road and for a time, the Gossen family maintained a trailer off Clear Lake Road near the Bain property. While at camp, children were free all day to do what they wanted. They would use other people’s docks and diving boards, and thought nothing of walking completely around the lake on their own.

On occasion, kids would float an old boat up to the beach and turn it over to play in the sand. Despite the sparse population, the families on the lake felt a sense of connection; indeed, many were related. Folks would gather at each other’s cottages and many on the lake called Nell Morrissey “Granny.”

On rainy days there was always a game of cards in progress at someone’s camp. Without television things were quiet and people checked in on each other. All the area kids would come to Mary’s when her mother Nellie made homemade ice-cream.

Mary says that many of the camps used to have dock houses to protect wooden boats from the sun. Every spring, people had to go out to look for docks that had been taken away by the retreating ice. Her cottage at 1009 Clear Lake Road is located on a cliff; after every storm they used to look over and say, “What did they bring us today?”

One very memorable event occurred after Hurricane Hazel in 1956. Mary recalls that water was flooding so rapidly across Clear Lake Road from the area on the east side known locally as Blueberry Mountain that the children could sit in the water at the big culvert and the rushing water would wash them all the way to the other end!

Barry Noland’s parents lived in Ajax, Ontario and worked in a munitions factory during WWII. They were familiar with the Cache Bay Bains, and with Clear Lake. As a child, Barry stayed at Nell’s (Granny’s) cottage every summer, and continued to visit regularly as an adult. When he was young, there were only some six other buildings around the lake. There were no organized events, so children spent days together outside, often swimming in the bay near the Bains’ cottages. He fondly remembers traveling to Field to the ice cream stand and COOP.

In 1958, Louis Legault was looking for lakefront property to house two recreational trailers. He bought a lot and small stick cabin at 1125 Clear Lake Road from Nora Somers. Louis removed the cabin to make way for two camps, one for the Legaults and a separate camp for his in-laws, the Serré family. In 1964, the Serré camp was removed and the Legault cottage has since been replaced with a full-time home for Louis Legault’s son Michael.

Michael recalled that his family would spend the entire summer at the cottage with their mother while Louis commuted back and forth to work in Sudbury. Often they would drive back down Clear Lake Road to meet him at Highway 17. Despite the cottage lot being full of berries, Michael and his siblings would often walk to Blueberry Mountain instead for berries so their mother could bake fresh pies. Bass and pike fishing was always good, and in the old days there were huge populations of tadpoles. He enjoyed the lake as a child and returned on retirement to build his full-time home.

In 1955,

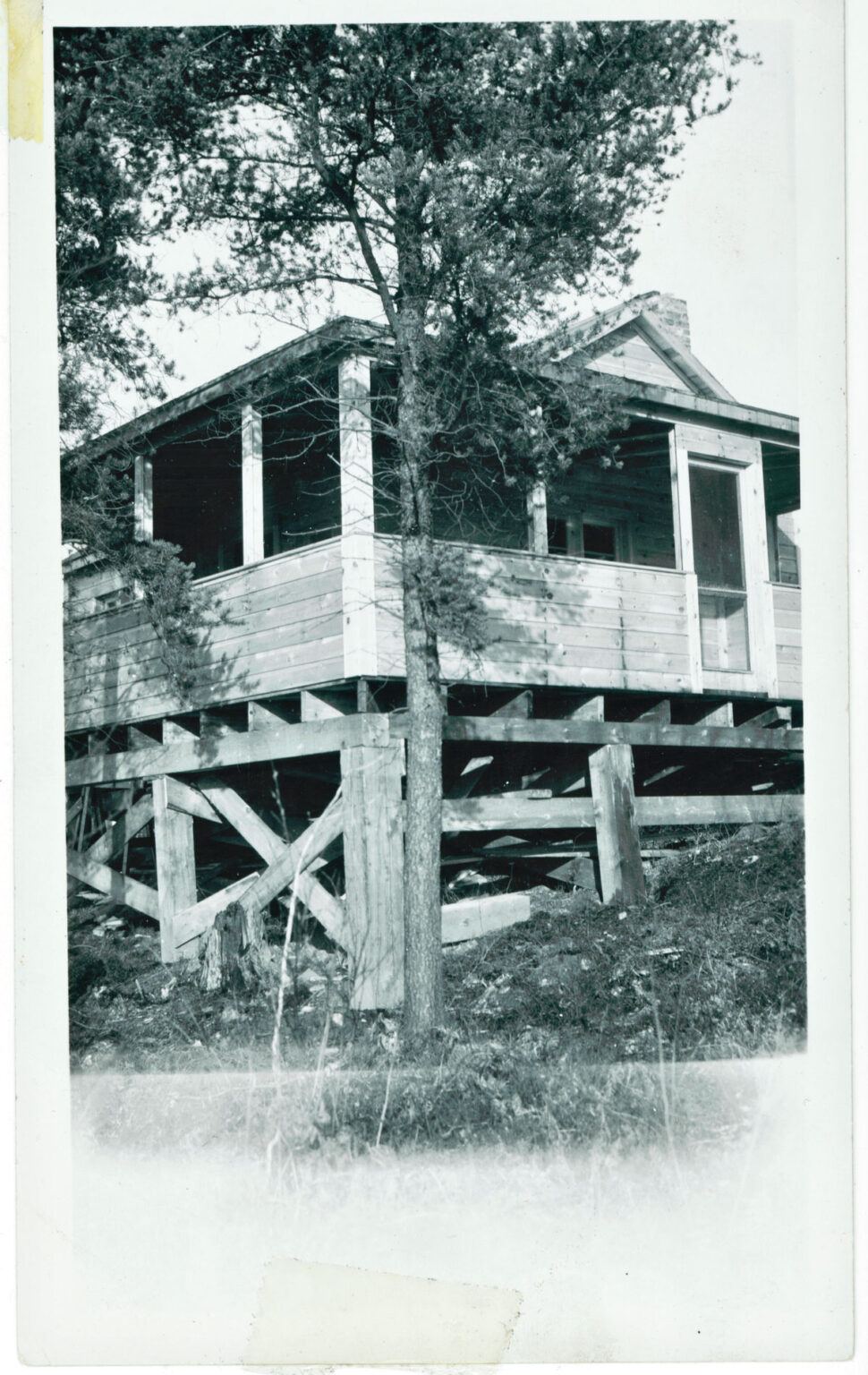

Jack Hope purchased the property at 1081 Clear Lake Road from Conrad Gervais. This property was first purchased and developed in 1947, and had passed through several owners, including the Field Lumber Company. Jack Hope, a professional forester from Toronto, purchased Field Lumber in 1956, and continued to operate it with his right-hand man Garfield Morrison until 1980.

Pat Hope, the youngest of Jack’s five children, reported that her family owned the cottage for 26 years. When they purchased the cottage, the family lived in Field, and moved to Sturgeon Falls a year later. The original cottage was for seasonal occupancy only; while it had electric service, there was no running water.

In 1967-68, the log siding and inside paneling were added to the original structure to winterize it. The chimney was bricked with an “H” monogram on the outside; an indoor bathroom, drilled well, sunroom and combination electric/wood stove were added.

In 1968, the family moved to southern Ontario. However, Jack remained at Clear Lake as a full-time resident. The family would commute to the cottage during the summers. To Pat Hope’s recollection, Jack was the first full-time resident on the lake. Initially, the Township of Field snowplowed only a short length of Clear Lake Road, so on arrival, Jack would drive to the landfill site at 1289 Clear Lake Road and snowmobile the rest of the way to the cottage. Eventually, snow removal was extended from Field to the Hope driveway.

Pat recalled spending Christmas 1968 at the cottage. Despite there being no group summer activities on the lake, July-August at the cottage was always a very busy time. Everyone had boats, kids enjoyed fishing and waterskiing with an old wooden boat and a 25 hp motor. Kids sailed and canoed, picked berries on Blueberry Island, dove off the rocks in the bay where the loons lived, and enjoyed picnics. Back then, there was open access to the beach and you could drive right to the water’s edge; in fact, some people drove right into the lake to wash their cars. That practice became controversial and was eventually stopped.

While there was yet no kiosk at the beach, folks could expect that a chip stand might be there. Pat’s mother was quite active and would often canoe the lake in the morning before the children were awake. The kids would wake up and go outside to sit on the dock in their pajamas, watching her return to the camp. Clear Lake had spectacular sunsets, perhaps due to pollution around Sudbury in those days!

Carole Anne Friedrich, who was still cottaging at the Somers’ camp at this time, recalled that the Hopes and her family were good friends, and she would often babysit the Hope children.

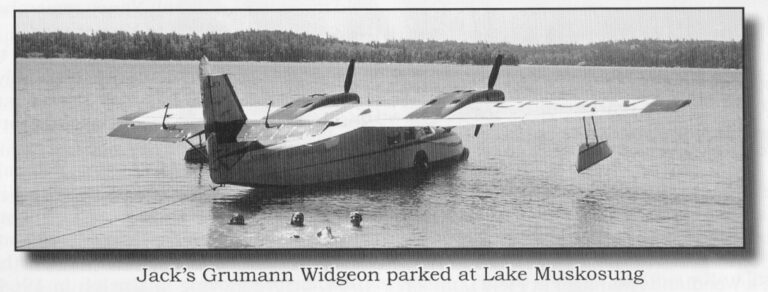

In the 1950s, Jack Hope maintained a spot on Lake Muskosung for his Grumman Widgeon aircraft. Rocks in Clear Lake made landing a big aircraft inadvisable, so when operating the Widgeon he would usually just fly over Clear Lake and tip his wings to alert the family to drive over to pick him up at Muskosung. Jack owned a second, smaller floatplane, a two-seater Stinson that could be parked on Clear Lake at his cottage. In 1958, during a labour strike at the mill, his Stinson was blown up with dynamite at the spot on Lake Muskosung.

When Francine Hurtubise and her husband Ronald looked to buy the Hope cottage in 1981, they fell in love with the bricked “H” monogram on the chimney, thinking, “This is fate,” and bought it. With the exception of some structural repairs, new windows and an added bathroom, most of the building remains unchanged. Outdoor alterations included removal of trees near the lake and replacement of the original big cement dock, where presumably Jack Hope had previously parked his floatplane.

The original owner of 1047 Clear Lake Road was Leonard St. George, owner of the hotel in Cache Bay. Leonard purchased the property in 1947. Claude McGrath and his wife Monique, along with friends Ed and Vivian Gascon, purchased the lot and cabin in 1978. Claude suggested that the cabin on that property may have been built as early as 1937; he discovered newspapers from that era inside the construction when he tore the cabin down.

On Claude’s arrival, the majority of the lots on the lake were occupied as summer cottages with only a few year-round homes. Cottagers were still using outhouses as opposed to septic systems, as water protection was not yet seen as high priority. The public beach was operational with an enclosed kiosk housing a kitchen, change rooms and indoor plumbing. A security guard collected user fees at the gate and there was a student lifeguard on duty. Hector Mayotte recalled that at one time swimming lessons were provided at the beach. Claude noted that during the 1980s, Catholic Mass was occasionally celebrated in the kiosk on Sunday mornings.

The lake was very busy in Claude’s early days. There weren’t many large boats, but waterskiing was popular and he and his son enjoyed it. Dr. St. George owned a 90 hp boat, and Claude recalls that the St. George and Mondoux boys could put on a good waterskiing show, complete with a two-storey pyramid!

An avid outdoorsman, Claude explored the local ATV trails; his red and white pontoon boat was a well-known sight on the lake. He also became an active member of the cottagers’ association.

South Shore Road Development

In the 1940’s, a dirt trail ran directly along the south shore from the intersection of Clear Lake Road to a small seasonal trapper’s cabin owned by Charlie and Millie Larocque in the marshy area just past the existing culvert on South Shore Road. Locals referred to it as “Charlie’s Trail.” Millie would sleep in a tent in the summer months and Charlie would use the cabin for winter trapping.

Gail Timm recalled that Charlie Larocque was grandfather to longtime lake residents Jenny Navid and her sister Pat Sayer. Gail also divulged that she and some others eventually knocked down Charlie’s original trapper’s cabin so that Millie could set up a small shack. South Shore Road still has a posted sign reading “Charlie’s Trail.”

Millie owned a wooden flat-bottomed boat that was often half-filled with water. She would regularly row over to the east shore to go berry picking in a patch on Blueberry Mountain, and would often take the blueberries back to Cache Bay to sell to travelers at the railway station. Because Millie enjoyed fishing so much, children referred to that area as “Millie’s Shore.”

Gail’s parents were Mary (Nellie) and Wellington (Dobby) Dobson. Together with her sisters Betty, Mary and Lois, they used to cottage at Granny Morrissey’s cottage at 999 Clear Lake Road beginning when she was five or six years old. They would travel to the camp along Clear Lake Road in the back of a pickup truck. The road was always muddy but in the spring it would be bubbling “clay boils” and if you threw something in them it would disappear from sight! In those days, Clear Lake Road ran even closer to Tanner Lake than it does today.

Gail recalled that in the old days, South Shore Road was simply a dirt trail that ran right along the shoreline. Children referred to that area as “New Moon Camp.” There were no buildings up on the hill as there are today. She fondly recalls walking up the road with her cousin Barry Noland to go fishing. They would catch grasshoppers and pick berries as she walked among the trees on the trail, which remained more or less undeveloped with only a few cottages for many more years.

As an adult, Gail often visited the lake to swim and picnic at the beach, and in 1959, she and her husband Harvey decided they wanted their own spot. The Timms had to use a small boat to check out the lots when they were looking to buy.

Harvey and his two sisters Dot and Gladys, who were married to brothers Boyd and George Stewart, purchased four undeveloped lots for trailers. In those days, regulations permitted the use of on-site trailers for up to two years to enable construction of a building. To get access to the lots, they installed a makeshift culvert on the trail at the frog pond. That culvert, an old burner from the Cache Bay mill, remained in use until it was replaced by the municipality some 50 years later.

In 1960,

Gail and Harvey built their cottage at 97 South Shore Road; it remains to this day. Back then, there were some undeveloped lots to the west of their property owned by three Arcand brothers. By 1969, South Shore Road was fully extended to its current length and configuration to provide access to all available lots, and most had been sold.

Dr. Richard Filion and his wife Colette purchased a cottage at 105A South Shore Road in 1968. He has many fond memories of their time there, and said the lake and beach were always beautiful.

An aircraft pilot, Richard used to park his Cessna 180 on the lake at the cottage and fly out for fishing trips. He recalled that Jack Hope and Carl Leblanc also used floatplanes on the lake. On one occasion, Carl’s plane struck rocks during a landing, but the plane did not sink and fortunately no one was injured.

Richard was also a scuba diver. He and several neighbours at the lake enjoyed diving in the crystal clear water. One very memorable event for him was a winter dive in 30 feet of frigid water in front of his cottage with members of his Sudbury Hammond Scuba Course.

Although he would spend only 10 years on the lake, action that he and few others took in 1970 would eventually lead to the formation of a cottagers’ association 16 years later.

By the time that the Timms bought, Highway 64 between Sturgeon Falls and Field was in use, Bell Canada had introduced rotary telephone service in the Field area, and electricity was widely available at the lake. Final paving of Highway 64 would be completed in 1977.

Gail’s daughter Sarah recalled that when she was a child before Charlie’s trail was moved to higher ground, the kids traveling by car loved the steep hill and quick drop off on the original trail. They called it the “Weeh! Hill.” In those days, a treat for the kids involved rowing across to the north side of the lake to fetch firewood to cook brown sugar and toast over an open fire. Going berry-picking on Blueberry Mountain could put down 70 quarts at times. The islands had some berries, but nothing like the mountain.

In Sarah Timm’s time. young children would spend time in the bush doing things like making houses in the bush or collecting clay for molding, while parents worked around the cottage. Sitting or relaxing in the sun was uncommon. For the Timms, cottaging was a summer activity only.

Sarah enjoyed going to the public beach. In her day, there was a gate at the roadway and people would be charged to park because it was so busy. There was a long dock out to a depth of four feet. In the mid-1970s, beachgoers could enjoy a kiosk with a jukebox and chip stand. On one occasion, a midway even came to town.

In the mid-1980s, Sarah was pleased to welcome the companionship of new young friends when a group of Sudbury families—Oystrick, Murnaghan, McLean and Fontaine—all bought cottages on Clear Lake.

The Timms refer to the islands on the lake as Bushy and Bald Islands. Interestingly, kids on the north side of the lake more often use the names Camp (or Thistle) and Blueberry. The outcropping of reeds in the northeast end of the lake was called Toothbrush or The Shoal. Some know other features of the lake as Frog Bay, Heron Bay, Blasphemers’ and the Whale (after a large rock resembling a whale in the Crown land at the southwest end of the lake). In the absence of any official names, who to say who is right?

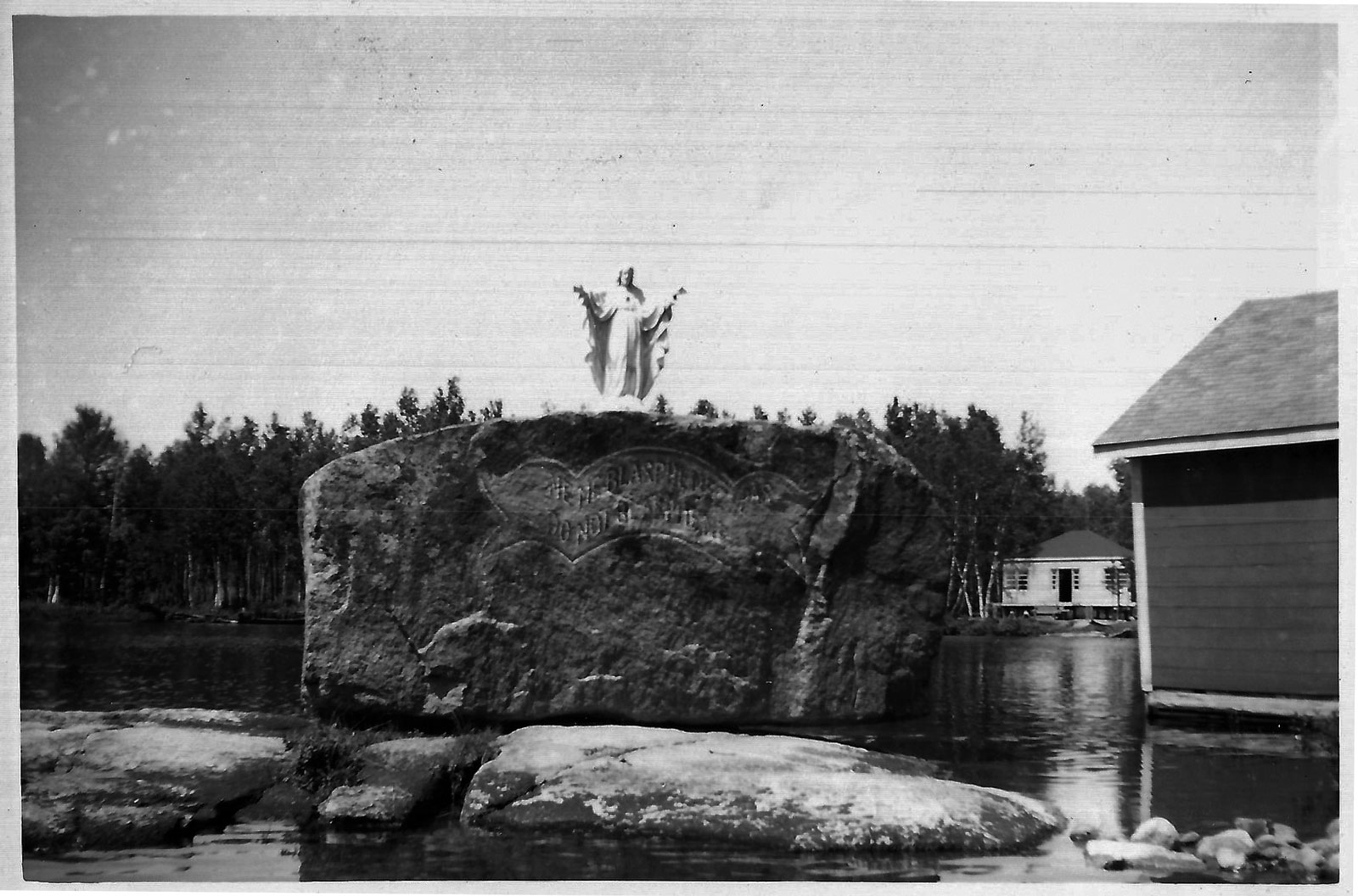

“NE ME BLASPHEMEZ PAS – DO NOT BLASPHEME.”

North Shore Road Development

Maurice Giroux’s father Henri hailed from Warren and worked for Labatts Brewery as the first beer salesman in Northern Ontario. Being friends with William Somers, Henri rented the original Somers cottage in 1934 and 1935. In 1935, he paid the Department of Lands and Forests $100 for a 10-acre parcel of land in the northeast corner of the lake that he could call his own. This tract of land running west along North Shore Road from Clear Lake Road has since been subdivided into several lots. Initially, the Girouxs built only a platform at 10D North Shore Road; a family cottage was built on the platform a year later for Henri, his wife Marie and son Maurice. Later, Maurice, his wife Annette and young son Paul enjoyed many summers there on the north shore of the lake.

Maurice recalled that in the early days, Clear Lake Road was very rough. If their family vehicle became stuck in the mud, they would call a local man, Mr. Chrétien, to tow them out with his horse.

During his time at the cottage, Henri Giroux often hosted large groups of guests, such as members of the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society. Maurice once collected 24 cases of empty beer bottles from the yard for his father one Monday after a big party. The original cottage has since been replaced by a new building now owned by Henri’s grandson Paul, who with his partner Marie Terrien, enjoys their activities that include forestry stewardship, carpentry, painting and swimming.

In 1942, Henri Giroux began subdividing his 10-acre parcel of land on North Shore Road, splitting it roughly in half with his brother Albert who built his cottage, Camp Albert, at 10A Northshore Road in 1944. Albert, and later his son Hector, operated a granite quarry in River Valley, making curling rocks. A few of those rocks are still visible in the grass beside the porch at 10A today.

Camp Albert is recognizable from the lake by a large erratic boulder on the shore emblazoned with the words “NE ME BLASPHEMEZ PAS – DO NOT BLASPHEME.” Albert Giroux’s wife Deliosa was a pious woman who had the rock painted in an effort to deter people from swearing. In the early days, a Sacred Heart statue was mounted on top of the rock.

Clear Lake in the 1940s was still only sparsely populated. Clear Lake Road near the site of today’s public beach was only about 30 feet from the shore, with a beaver dam to the east of the roadway. No effort had been made to open the beach to the public. It was heavily treed and had only about a 30-foot opening at the roadway.

Things changed in the 1950s when Maurice Giroux’s uncle, a businessman and lumber worker, used his bulldozer and truck to push the beaver dam back away from the beach to create a larger clearing. Carole Anne Friedrich recalled that in the 1950s the beach area was more clay than the sand that exists today.

According to Hector Mayotte, before 1950 Clear Lake Beach had not yet caught on as a public beach. Local residents often used a beach on Lake Muskosung for swimming until access was interrupted by new logging operations. Activity at Clear Lake Beach really flourished in the 1960s and 1970s. It became well known, with people coming for daily swimming from as far away as Sudbury.

On one occasion, Maurice Giroux counted 152 cars parked along the road near the beach. Clear Lake Road itself was not relocated back up onto the hill at its present location until about 1985.

Outhouses, hauling water, ice boxes and wood fires were the norm for early Clear Lake cottagers. Folks would often maintain an icehouse or icebox with insulating sawdust to keep food and drinks cold. Food and ice blocks could be purchased in Field.

Henri Giroux had passed away by the time power became available in the 1950s. His widow Marie, being the first person on Clear Lake to request an electrical hookup, was required to find a second prospective customer before power would be provided.

According to Hector Mayotte, in 1953 Aurele Quenneville purchased a block of land encompassing the small bay on North Shore Road located to the west of the Giroux property. This block was subdivided into five lots (30-34 North Shore Road), most of which were used primarily for hunting. John Kurchak’s log cabin was situated on the point and Bob Carré built a cottage at 34 North Shore Road.

Sometime around 1961, the Carré cottage burned down. Hector then purchased that vacant lot and built a cottage in 1964. In 1990, he replaced the cottage with a new full-time home.

In the 1950’s, Bains, Dobsons, and Nolands were living on the lake’s eastern shore; North Shore Road was opened up only to the hill near present day 148 North Shore Road. Beyond that point it was bush only. The last visible cottage was located at 88 Northshore Road.

Carole Anne recalled that nuns from the church in Field occasionally spent time in the summers in the area of 94 Northshore Road. A stone grotto with a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary stands by the shore at that location. Darlene St. George reported that the grotto existed when she and Roger purchased the property in 1990. While she is unsure of its origin, she continues to maintain it to this day.

An old log cabin stood on the point at 46 North Shore Road, then owned by John Kurchak. He would often yell at Carole Anne and her sisters when they were pole-rafting past his cabin, but on one occasion he happened to be holding a shotgun. It scared them silly, and they paddled out so far they could no longer touch bottom!

Garfield Morrison’s son Gordon recalled that Jack Hope always took issue with people calling the lake “Clear Lake.” He would always remind people that the proper terminology was “Bain Lake.”

Garfield was general manager at the Field mill and good friends with Jack Hope. The Morrison family was raised in Field and then moved to Sturgeon Falls. During the 1950s and 1960s they were regular visitors at the Hope cottage. In 1983, Garfield purchased a vacant lot at 10C North Shore Road from Maurice Giroux. The land was very low, requiring extensive backfilling that had made it slow to sell. Garfield built a three-bedroom cottage and became an active member of the community and the cottagers’ association during his time at the lake. Gord Morrison took possession of the original cottage in the 1990s; it has since been extensively remodeled.

Gord recalled that the bass fishing was so good you could cast bait from a fly rod into the lake, leave it unattended, and come back to find a fish every time. During electrical storms, with so much rock around, he often saw flashes of electricity across the floor from the electrical outlets at the old cottage. Decades later, hydro interruptions in the lake area are still quite common.

By 1969, North Shore Road had been opened up only to the area of 148. Hector Mayotte and his family maintained a multiple-bed hunt camp located in the bush past the end of the cleared roadway. The camp was eventually renovated into a full-time home at 168 North Shore Road.

That same year, Carole Anne Friedrich became aware that the Ministry had surveyed additional lots to the west of 148 North Shore Road that were coming up for sale. She and seven others, including Mayotte, Navid, Steadman and Tremblay, quickly submitted offers to purchase. Their offers were accepted; at that time lots sold for around $500 plus $60 in survey costs.

One of Carole Anne’s relatives who worked in the logging business used a chainsaw and heavy equipment to provide the first road access to the new lots before any permit could be issued. That road has since been upgraded by the municipality.

After spending early years renting on the lake with her parents, and being an outdoors person with extensive knowledge of the lake and surrounding area, Carole Anne was convinced that she would spend her life on Clear Lake as a full-time resident. She has also played a very active role in the community and the Clear Lake Cottagers’ Association.

In 1971, 10B North Shore Road was severed from Albert Giroux’s property, and was initially owned by Albert’s son Laurier. In 1995, the remainder of Albert Giroux’s original property was severed into two lots: 10A North Shore Road, and a lot with no assigned municipal address that remains undeveloped and encompasses the “DO NOT BLASPHEME” rock.

In 2000,

Nicole (Quenneville) and Winston LeMay replaced the old cottage at the west end of the beach at 10E North Shore Road that had been owned by Nicole’s mother. The new building, of modular construction, was brought in on two trucks and assembled on a new concrete foundation.

Catherine Bacque and Alan Hardiman, who purchased 10B North Shore Road in 2002 with the encouragement of Paul Giroux, reported that during a recent renovation of the foundation, workers discovered a pile of old electric wiring and charred timbers four or five feet underground. Whether these were signs of an earlier structure on the site or just a pile of trash remains unknown. Catherine raises butterflies from eggs found on the many milkweed plants she has cultivated on the property and enjoys swimming from Toothbrush Island back to the cottage. Alan enjoys building decks, gazebos and other structures, and admiring Paul Giroux’s handiwork. Clear Lake is an ideal, peaceful location for them to write music for films, videos, commercials and performance.

“You either love the pipes or hate them.”

Bob Jolley reported that he and his wife Joyce purchased 116 North Shore Road in 2003. The 1959-era cottage and summers at Clear Lake have formed an integral part of growing up for all of their grandchildren. Getting together at a cottage with access to water sports and nature has provided special opportunities and created memories that will last a lifetime. Everyone brings something different to the lake. Bob says the folks at “J&B on the Rocks” have introduced bagpipes and family parades. Rumour has it that “you either love the pipes or hate them.” If you are the latter, Bob and Joyce offer their sincere apologies!

Clear Lake Cottagers’ Association

Up until the 1999 West Nipissing amalgamation, Field Township Council was responsible for governance and oversight of the Clear Lake area. As the public beach became more popular in the 1970s, a kiosk was built and more activities were added. A snack bar, change rooms and indoor plumbing would remain in use for a while but would be discontinued by the mid-1980s. In 2003, when the building fell into disrepair and residents complained about the state of the public beach area, West Nipissing reduced the building to an open kiosk with outhouses.

One very controversial activity Council sanctioned during the 1980s was an annual winter carnival, when vehicles were allowed to operate on the ice at the beach. Lake residents spoke out at Council and the carnival was canceled in 1989.

On August 20, 1970 a tornado touched down in the area damaging buildings and causing one fatality in Field. Fortunately, Clear Lake escaped injury or critical damage.

As the population and activity increased on the lake, so did concerns over pollution. In 1970, Dr. Filion, Dr. Patenaude, Jack Hope and Avro Korell distributed a letter to residents hoping to raise awareness. The letter asked that residents employ higher standards of sanitation around the lake and suggested that a moratorium on building might be necessary. No such moratorium, however, was enacted.

In 1978, Field Township Council joined a West Nipissing Municipal Association plan to implement cross-country ski trails. Two years later, a chalet named “Auberge des Voyageurs” was built on Clear Lake Road north of the beach. While the building remained in use for some time, the full project did not proceed. During the 1980s, Claude McGrath and Raymond Faubert organized Canada Day corn roasts at this building, with races and games for local children. The Auberge was eventually sold in 1993 and renovated into a private residence.

Over the years, the area around Field fell victim to many floods and fires. In 1979, the Sturgeon River watershed experienced the worst flooding in its history. Clear Lake was not remarkably affected. But by this time, Clear Lake residents were becoming increasingly concerned that safeguards were required to protect the lake.

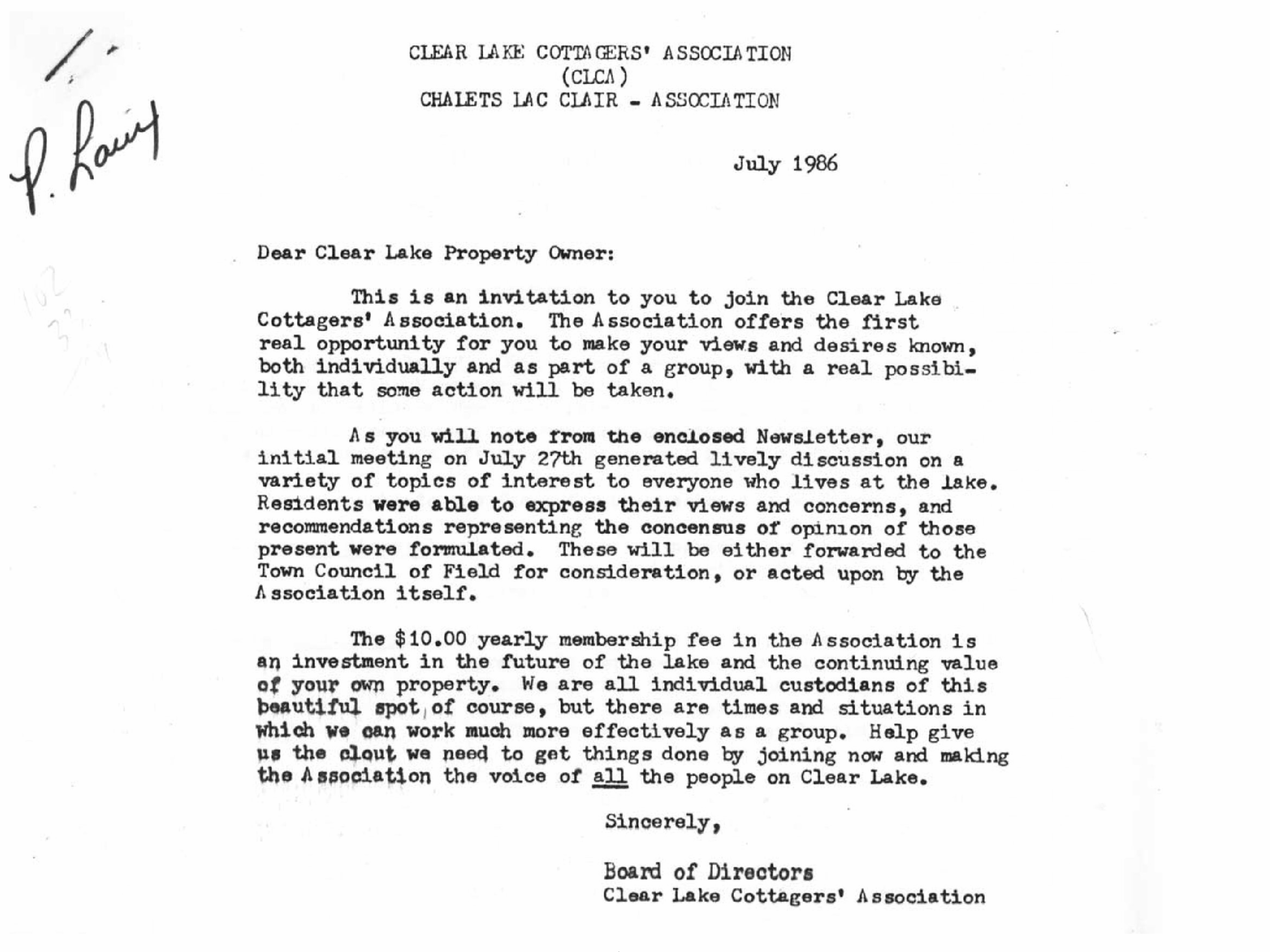

In 1986,

Dr. John Lynch, Garfield Morrison and Pauline Prieur organized a meeting at the Auberge des Voyageurs to discuss creation of a residents’ association. Steven Friedrich assisted with incorporation and in 1987, the Clear Lake Cottagers’ Association of Field (CLCA) was established by charter.

Dr. Lynch would be the first association president, and Garfield Morrison agreed to coordinate with Council, identify needs for safety buoys, look into water testing and monitor the beach.

Within a short period of time, Claude McGrath began marking hazards on the lake with 15 buoys. Over his 30-year tenure, he was assisted by numerous other individuals and posted an increasing number of CLCA buoys until the program was discontinued in 2020 due to federal regulations and liability concerns. In 2004, CLCA joined Ontario’s Lake Partner Program to monitor and report on water quality.

Up until amalgamation in 1999, CLCA had limited success relating with Field Township Council over lake issues. However, Claude McGrath reported being encouraged that West Nipissing Council was much more receptive and responsive to CLCA needs than their predecessors.

In 1987, the Ministry of Natural Resources studied the potential of stocking Clear Lake with pickerel. Two years later, CLCA objected on the basis that a similar project on Lake Muskosung had been detrimental and led to the lake being fished out.

In response to CLCA concerns regarding beach security, Council employed numerous initiatives, including establishing a separate boat-launch road, placing rocks between the grass and the sand, and installing the locking gate that exists at the beach entrance today. In 1997, at the request of CLCA, the old beach road that still enabled direct access to the beach from North Shore Road was permanently closed. This was done to prevent cars from entering the beach area from the west side.

In 1991, an outside group, Planterior Corporation, approached Field Township Council seeking approval to establish a nine-hole golf course adjacent to Clear Lake Road east of the public beach. Although some CLCA members were supportive, CLCA opposed the proposal, which was eventually rescinded by the proposer to avoid the cost of an environmental assessment.

In 1995, the Canadian National Railway ceased operations to Field.

In 2010, CLCA joined with other groups in successfully opposing a quarry development on Clear Lake Road. More than three decades after its establishment, CLCA remains active advocating on behalf of the lake community.

In 2018, CLCA members present at the annual general meeting reviewed 14 unofficial names that had been suggested to rename the beaver pond located behind the landfill adjacent to North Shore Road. Perhaps predictably, the winning entry was “the Beaver Pond.”

Conclusion

Today, there are 93 established lots on Clear Lake. The lake has a surface area of 197 hectares, a perimeter of 8.2 km, an average depth of 5 meters and a maximum depth of 45 meters. While it may not be as pristine as it was in 1900, it still deserves the name Clear Lake and the cottagers’ association remains active and strong.

Looking back, it is clear that the Bain, Somers and Giroux purchases in 1925, 1932, and 1935 kick-started development on Clear Lake. Once those original blocks were populated, individual lots, often purchased by friends or relatives, began popping up, first along Clear Lake Road, and then along the eastern portions of the other two roadways.

North Shore and South Shore Roads were originally much shorter than we know them today, and each was developed in separate phases with much of the development happening in the early 1960s. The opening up of the last seven lots on North Shore Road began only in 1969. By 2000, all lots were in use.

Things change. Keeping a cottage in the family may no longer be the norm. Over the past two decades there has been a remarkable change in our Clear Lake community. Each owner who leaves takes a bit of lake history with them. CLCA recognized this reality when implementing the Clear Lake History Project. We would like to save that history. The Lake Committee would like to thank those folks who took the time to share experiences and provide a basis for this article.

Comments or recommendations regarding content may be addressed to:

history@clearlakecottagersassociation.ca

To visit the Clear Lake Cottagers’ Association of Field website follow this link: